“Prose fiction is something you build up from 26 letters and a handful of punctuation marks, and you, and you alone, using your imagination, create a world and people it and look out through other eyes. You get to feel things, visit places and worlds you would never otherwise know. You learn that everyone else out there is a me, as well. You’re being someone else, and when you return to your own world, you’re going to be slightly changed.

“Empathy is a tool for building people into groups, for allowing us to function as more than self-obsessed individuals.”

—Neil Gaiman, “Why our future depends on libraries, reading and daydreaming”[1]

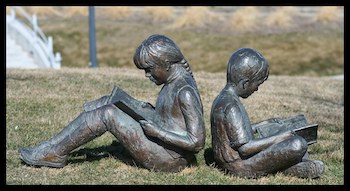

My piece today is an ode to reading and to books, and to the rich inner life they give us. In this time of shrill and angry voices, and the attempts to drown out differing points of view, books are a light in the darkness, a point of sanity.

You pick up a book and start to read. Within minutes—even less, in the hands of a good writer—you are immersed in another world. There is no feeling like the luxury of sinking into a good book. You’re starting on a journey and you’re not quite sure where it will take you. The busyness of the world, the soundbites, the unending social media feed, the 24-hour news cycle fade into the distance. The book gives you an oasis of quiet.

Reading is a deep dive into another world, a place or time you may not be familiar with. By the time you finish, you will have learned something new, become a part of lives that are probably unlike yours. Reading, especially reading fiction, is sometimes dismissed as an escape from the real world. In one sense, maybe this is true. But what it gives you is invaluable. Books, by taking us into another world, help us walk in someone else’s shoes. And in doing so, they create a sense of empathy—something sorely lacking in today’s polarized world.

I was struck by a phrase that I found in the Financial Times’s list of best books of 2023: “a poetic book about slavery”. It seems a contradiction in terms. How can anything poetic come from slavery? But that is the genius of writers: they can, without sugar-coating the pill, as it were, pull out the beautiful and the moving from things that are horrifying, and by doing that, find the humane in the inhumane. In other words, writing connects us to what we all have in common as human beings.

Think about books such as Anne Frank’s diary; Marlon James’s The Book of Night Women, set during the slave rebellion in Jamaica; Bapsi Sidhwa’s Cracking India (also published as The Ice Candy Man), set during the Partition of India and Pakistan; Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun, about the Biafran War in Nigeria; or ex-MP Fawzia Koofi’s memoirs about living through the seismic changes in Afghanistan (The Favored Daughter—One Woman’s Fight to Lead Afghanistan into the Future). At the centre of these books are ordinary people living through extraordinarily challenging times. And because we identify with them, we begin to understand their circumstances and the reasons for their actions.

Now with more books available in translation, our exposure as readers has widened considerably. I can draw up a long list of books that have taken me to places I did not know too well. Books such as Beyond the Rice Fields by Naivo about a woman and her slave in Madagascar; The Shape of the Ruins by Juan Gabriel Vásquez that introduced me to a part of Colombia’s history; Mother’s Beloved—Stories from Laos by Outhine Bounyavong, covering three decades in the lives of Laotians; How the One-Armed Sister Sweeps Her House by Cherie Jones, a story about a young woman in Barbados; The Death of the Perfect Sentence by Rein Raud, a novel set in the days preceding Estonian independence; and Iep Jāltok—Poems from a Marshallese Daughter by Kathy Jetn̄il-Kijiner, who writes about the nuclear tests in the Marshal Islands. These books gave me a chance to understand life in these diverse countries.

Reading reminds you of how crucial diversity is. A uniform world where everyone thinks the same way would be extremely boring, not to say unhealthy (think of Ira Levin’s The Stepford Wives). We might not share the same beliefs, but—and this is something that seems to have been forgotten these days—the world is big enough to accommodate divergent points of view. We do not need to shut other voices down simply because we disagree with them. It is only by understanding “the other” that we can build bridges, something we sorely need to do in today’s world.

And books are a way into that understanding.

I cannot stress enough the importance of reading, and how vital it is for people—especially for children—to have an easy and unrestricted access to books. I was lucky as a child because my parents encouraged me to read without placing any limits on what I read. It is the best gift you can give—reading expands the imagination, and gives us an ability to inhabit other worlds, imagine other lives. And a reader is never lonely.

Read widely, and you will never be disappointed.

[1] The Guardian, 15 Oct 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/oct/15/neil-gaiman-future-libraries-reading-daydreaming

Note: I am going to be taking a break for the holidays and will be back on 6 January. Wishing you all happy holidays and a wonderful New Year filled with good reading!

Well said Suroor! I have nothing to add , other than echoing “how can anything poetic come from slavery “? I think of Alan Paton in Cry The Beloved Country as I read this. He described the oppression of South Africa apartheid in that poetic way also.

Yes, there are so many books like that. Another of your suggestions on my list!

Oh- you must read Cry The Beloved Country