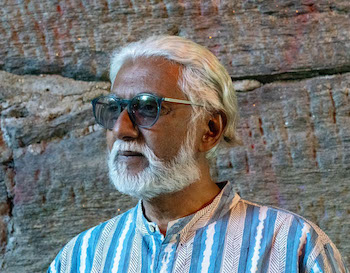

Krishna Candeth is an Indian writer, poet and filmmaker.

His first novel, All Stray Dogs Go To Heaven, was published in 2023.

Before going to New York to study filmmaking at Columbia University, he made several documentary films for Indian Television, including a film on the romance of the monsoon in India; one on how Indians through the ages have used architecture to cool their homes; and a whimsical look at the evolution of the tail from fish to spider monkeys and its vestigial remains in man.

Krishna has also taught English at various schools including The Doon School in Dehra Dun and India School, Kabul, Afghanistan, in the late seventies.

His poetry has been published in the UK and the United States.

Talking About Books interviewed Krishna on his novel, and the importance of telling stories.

TAB: All Stray Dogs Go To Heaven is your first novel, and you’re now in your 70s. Why did you wait so long to write it?

KC: Thanks for reminding me how old I really am! I wish I knew the exact answer to your question, though. There are some stories that you carry with you for years, that roll around like tiny marbles in your head, waiting for the right time to emerge and assume a life of their own. As I say in the preface to the novel, life has a way of carrying us off in all sorts of unpredictable directions. I also have this unfortunate tendency to leave things half done and go charging off to attend to something else that has caught my imagination. Not a good thing to do when you need to complete something you’ve begun!

The important thing is that I finally sat down and wrote the novel. And I wasn’t distracted. And it’s a novel as I intended it to be. And it’s called All Stray Dogs Go To Heaven.

TAB: The book is bursting with stories. How did you put it all together?

KC: Anything writers say about their own work should be taken with a small degree of suspicion. They think they’re writing about one thing and then discover, in the course of writing, that it is about many other things. So even though I may have started out with the idea of telling one story I’m sure I realized very soon that the story I wanted to tell was part of an untold, longer story, and that stories have a way of linking up and connecting, and, sometimes, even bleeding into each other. I like to think of Stray Dogs as a story about stories, a way of telling stories that never end but lead instead to more stories! I think it all has to do with the form of the novel. It is so wonderfully elastic—it expands, it absorbs, it accommodates everything.

A good novel doesn’t follow a recipe. Sure, there are ingredients in it but how you use them is entirely up to you, and what you end up with may be a totally new recipe that you will never find in any cookbook.

India has such a rich storytelling tradition ranging from ancient epics to regional folk tales. They tell age-old stories with new twists and turns. There are texts in which some stories are repeated, once briefly and then, later, at length. Or there are stories within stories, like Chinese boxes, each fitting into the next larger box. A lot of old Indian tale collections were taken abroad by merchants and travelers, and became the sources for the Arabian Nights and a lot of European fairy tales.

Joan Didion says somewhere that we tell ourselves stories in order to live, and that is literally true because we know how Scheherazade postpones her execution every night by telling the cruel king endless stories.

Putting the stories together wasn’t as hard as it first seemed. I knew there were stories I had to tell, and so I worked on some of them separately. Afterwards it was just a question of finding the connective tissue that would allow them to join up with the main body of the novel.

TAB: I am fascinated by Nitya’s aunts and their relationships. Where did these characters come from?

KC: Ah, aunts! Who can tell what mood they’re in or what they’re up to?! Nitya’s aunts grew up in a matrilineal family in Kerala in an insulated, obsessive world that they breathed and created for themselves.

As a child I remember being surrounded by aunts who were larger than life, and perfectly beastly to me, one and all! It was only years later that I realized how brilliantly gifted they were, each in her own mean, generous, hurtful way.

Some of Nitya’s aunts carry traits that I recognize in my own aunts but as characters they are amalgams of women who were born in a particular place and in a family that shaped their needs and their ambitions.

TAB: The novel has a section where some of the characters live with Naxalites in the jungle. Your description feels very real. How did you do the research for this?

KC: I spent a few weeks in the Bastar region of Chattisgarh in Central India which for centuries has been the home of the Adivasis—the earliest inhabitants of the land. It is a region of great pristine beauty—caves and forests and waterfalls—but as it turned out it wasn’t a particularly good time to visit.

The discovery of minerals—iron ore and coal and gold and lithium—in the region had led the state governments to try to buy out and relocate the tribals, and lease the land to corporate interests. So the battle lines were already drawn, and anyone who was fighting for the right to stay on his land was branded a Naxalite.

I was interested in tribal practices, superstitions, and funerary rituals, and during my visits to various villages I got a wonderful sense of the daily lives (and deaths) of the people who inhabit the region.

The Gonds for example, believe that all humans have two souls—the life spirit and the shadow. If, after death, the shadow is allowed to return to its home it is likely to harm the surviving relatives of the dead person. So a stone or wooden memorial is erected in his memory, and it is often engraved with birds and animals, and anything else he or she may want to be remembered by. And since they believe in life after death, the tomb or the memorial site is heaped with things the diseased used in daily life—his charpai and rice beer and various tools and utensils.

I would have liked to have stayed longer but it was clear that my guide was worried for my safety, especially on some of the longer trips we did together. In any case, I’ve always believed that even though it’s often tempting to carry on with the research, there comes a time when, armed with the information you already have, you must simply take the leap and begin writing.

TAB: Writing a novel and making a documentary have something in common: in both you are telling a story. How does your approach to the two media differ?

KC: I suppose at a very fundamental level, we are in the world of words as opposed to images. With writing, the joy comes from putting words together and finding just the right combination to convey an image or an idea. The image, on the other hand, is a physical presence; the man or woman doesn’t have to say a word—the way she sits or stands or smiles or moves about already tells us a lot about her, equal, you might say to a whole page of tortured writing!

Perhaps the question is a bit unfair because in a novel you are generally telling a fictional story; some novels, of course, are based on real events and have a plot and characters just like in a novel but they tend to be classified as literary non-fiction.

A documentary, on the other hand, is embedded in the real—it is almost always about real persons or places or events in the present or in the past. The difference, of course, is that here, one writes with the camera—a pan across a landscape or a movement towards or away from the subject affects the viewer in a way that is difficult to explain.

TAB: You are a poet. What inspires you to write poetry?

KC: The good thing about poetry is that it is portable—you can carry words, and rhymes, and other bits and pieces in your head wherever you go. Unless, of course, you’re writing an epic poem which might make things slightly more difficult.

Sometimes you have an idea and you don’t know what to do with it. You wonder whether you should work it into a poem or flesh it out into a story. Nice dilemma to be caught in! Some days you wake up with what you think is a good combination of words in your head. The real inspiration then comes from deciding what you’re going to do with it. And what started off as a nice combination of words breaks up or gets multiplied into new ideas and new combinations and becomes a whole new poem.

There are times, of course, when the wonder and pathos of all the little things that happen in one’s life pushes you into thinking of the poem that may be lurking there, and you try and draw it out. Conversely, the sheer scale of suffering as we have witnessed over the last two years in Gaza makes you think of the inadequacy of words to describe the misery and sorrow of thousands of people. And yet one has to try and find words that can describe what you feel.

TAB: When did you start writing? Is it something you’ve always done?

KC: When I was nine or ten years old I would write short “stories” often just a paragraph long called “A good lunch” or “A bad haircut” etc. Those are not real stories, one of my aunts would say, What you really deserve is a bad lunch and a bad haircut.

Later, like everybody in their teens, I felt that only poetry, because it was such a concentrated form, could really reflect all the torments that I was going through!

Then I got very interested in film and started writing screenplays, and apart from keeping a diary from time to time, never really pursued the desire I’ve always had to write a novel. Which brings me back to the beginning. I’m in my seventies now and quite happy playing with words again and combining them in new forms, and hoping, of course, that somewhere along the line it will make sense to all those who read them.

TAB: Thank you, Krish, for your wonderful take on stories. I loved the way you wove stories together in your novel and created some unforgettable characters. Looking forward to your next one!

Pingback: All Stray Dogs Go To Heaven: Krishna Candeth – Talking About Books