Written with Will Millard

Published by Witness Books, 2025, 312 pages

“When I was young, if you had granted me one wish, I probably would have chosen to be invisible. If I was invisible, I rationalized, then I could get as close as possible to the earth’s most elusive creatures. Moreover, I could comfortably evade all the things that troubled me most in the human world too.”

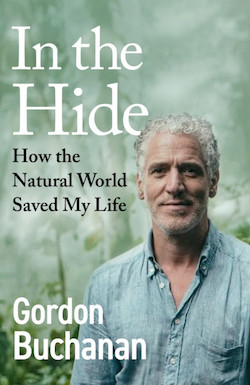

If there was anyone’s job that I envy and covet, it is Gordon Buchanan’s. A wildlife photographer and presenter of BBC documentaries, he has hung out with wolves, bears and elephants (and almost been eaten by a polar bear, but more about that later).

These are his memoirs.

Buchanan grew up on a council estate in Dumbarton, Scotland, with his two brothers and a sister. His parents split up when he was young, and his mother raised the four children on her own. She moved the family to the Isle of Mull, which Buchanan loved. He was free to roam the island, and he made friends for life.

But there was also darkness here, something that he only alludes to in the first half of the book. When writing about his childhood in Mull, he refers in passing to a need to be out of the house as much as possible. The reason was his stepfather Alastair, who was violent with both his mother and the kids. After one particularly horrible beating, his mother threw him out, and he wasn’t a part of their lives anymore.

The scars remained, and Buchanan suffered from depression. Initially, he countered it by saying yes to any job that came up, justifying it as part of his “grand strategic plan”. But the truth was that he needed to keep busy to avoid facing his demons. Eventually, he realized he had to deal with them, and got help. He also met his wife, Wendy, who seems to be a steadying influence in his life.

These personal revelations come in the second half of the book. In his early descriptions, his childhood and youth in Mull seem almost idyllic.

Buchanan’s career as a wildlife cameraman began when he started working for Nick Gordon, a wildlife photographer. He went with Nick to Sierra Leone on a project as his assistant. These were the days before the internet, so researching a place before you got there was much harder. Buchanan, who had spent his entire life in Scotland, was now in a completely new environment. Not only was he in Africa, but he was in a village in the jungle—as far away from Mull as you could possibly get.

Working with Nick taught him a lot, and eventually he started working as a wildlife photographer himself. He joined the BBC, and presented the Animal Family and Me series. The point of the series is to understand animals in their own habitat, as they go about their lives. This means that the presenter has to spend time with them—or at least, in their vicinity—until they accept him and behave normally around him.

One of my favourite parts of this book is his description of getting close to Arctic wolves. (It’s also my favourite episode in the series.) Wolves have a bad rap in folk tales—they always seem to be the baddies. As Buchanan puts it, they stand for bad human behaviour. In reality, wolves are extremely intelligent animals. They are curious about this human who sets up camp in their vicinity. Once they realize he is not a threat, they accept him almost as one of the pack.

For me, the thrill of watching Buchanan’s documentaries has always been the magic of a human connecting with a wild animal—the slow building of a relationship until the animal trusts him. And sometimes, even more. The wolf pack went hunting without leaving an adult behind to guard their pups because they knew Buchanan was there. That kind of trust is a real privilege.

It doesn’t always work out, though. Filming polar bears was always going to be difficult—they are notoriously aggressive, not to mention seven feet tall and weighing 200 pounds. So a Perspex cube was constructed, built to withstand the pressure of a bear on the rampage. Buchanan sat in the cube, thinking that the bears would head to the waterhole in the ice to catch a seal. But the female bear who turned up caught a whiff of human and ambled over to what she must have thought would make an easier meal.

It must have been quite an experience: to be in a transparent cube with 200 pounds of bear battering it, trying to open it so she could get to the human. Buchanan stayed incredibly calm throughout—at least, on the surface—and kept filming and talking to the camera. Finally, the bear gave up and left, much to Buchanan’s (and the viewers’) relief.

One of the things he writes about is how we humans see the other species that we share the planet with. We tend to judge them by our own standards and are amazed when they can do what humans can. I’ve always believed that all animals are intelligent—many of them can do things that humans are incapable of—and it is arrogance on our part to claim otherwise. As Buchanan puts it, “The creatures around us are inherently ‘intelligent’ by virtue of the fact that they are still here with us—survivors of all those evolutionary twists and climatological curveballs.”

Buchanan comes across as honest, thoughtful and passionate about the natural world. This book is a treat, especially for someone who loves wildlife.