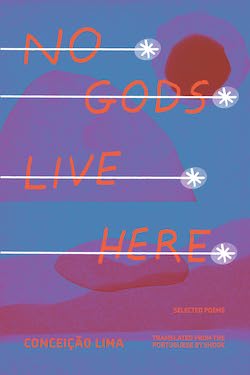

Translated from Portuguese by Shook.

Published by Phoneme Media and Deep Vellum, 2024, 255 pages. The original versions of the books from which the poems are taken were published in 2004, 2006, 2011, 2014 and 2024.

“The dead ask:

Why do roots sprout from our feet?

…

What was this kingdom that we planted?”

—From Plantation

“The enigma is some other thing—no gods live here

Just men and the sea, immovable inheritance.”

—Archipelago

Situated in the Gulf of Guinea, near the western coast of Africa, São Tomé and Príncipe is the second smallest African country, and the smallest Portuguese-speaking one. The two islands and their archipelagos were uninhabited until Portuguese explorers discovered them in 1470. They were then colonized by the Portuguese, and people were brought in from western Africa to work as slaves on coffee and cocoa plantations. São Tomé and Príncipe has been a sovereign country since 1975.

These poems by Santomean Conceição Lima draw on this heritage—the history, the geography and the people of São Tomé. The dead and enslaved are still there, still present.

In Afroinsularity, she writes about the Portuguese who came to the islands: “navigators and pirates, / slavers, thieves, smugglers, / simple men, / rebellious outcasts too, / and Jewish infants / so tender they withered / like burnt ears of corn.” And, of course the African slaves, slaves that often died working the plantations.

“And there were living footprints in the fields slashed

like scars—each coffee bush now breathes a

dead slave.”

I loved Dark Song to My Roots. Lima laments the fact that she cannot find her grandfather’s village, the village from where he was taken. He did not leave his children the name of his “great lost river”. She imagines him living on this island, far from what is familiar: “Scattered in an oasisless blue, / perhaps my first grandfather cried / a long, free, useless cry”. Her roots may be obscure—she does not know where her grandfather came from—but they lead her back to Africa, to the continent as a whole.

Lima’s poems are beautifully observed. The Vendor is about a boy:

“His eyes flicker like fireflies

in pursuit of customers.

…

At the end of the day, frugal,

he returns the bag of coins to an adult

and becomes his age again.”

In the collection from her book Elemental Ghosts, she writes about those who fought against colonialism, including Kwame Nkrumah from Ghana, Patrice Lumumba from Congo, Julius Nyere from Tanzania, Amílcar Cabral from Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde, and Alda Espíritu Santo from São Tomé.

The poems vary from very short ones to those that are several pages long (like Dark Song to My Roots). They are selected from Lima’s body of work and are arranged chronologically in a bilingual version, with the original Portuguese on one side and English on the other.

Beautifully translated by Shook, the poems are evocative of São Tomé and Lima’s love for her country, her effort to understand it and therefore to understand herself.

A poet well worth discovering.