Translated from Portuguese by Garry Craig Powell

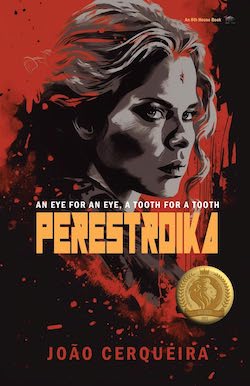

Published by 8th House Publishing, 2024, 394 pages. Original version published in 2024.

This is the portrait of a dictatorship and its aftermath, told through the lives of ordinary people as well as those in power. Set in a fictional Eastern European country called Slavia, the first part of the novel takes place in 1978, during the dictatorship; and the second in 1989, when the USSR government under Mikhail Gorbachev launched Perestroika, which eventually led to the fall of several communist regimes, including the Slavian one. We get a 360-degree view of the country, with short chapters focusing on the various characters and their lives.

The book starts with an art exhibition in the capital Tiersk, an exhibition inaugurated by Alfred Ionescu, the president. Invitees include high officials of the regime, diplomats—basically, the great and the (not so) good of the country. This is when we meet many of the characters we will get to know during the course of the book, including Pietr Schwartz, the Chief of the Secret Police; Zut Zdanhov, the People’s Commissioner for Culture and Propaganda; Helena Yava, the People’s Commissar for Education; Igor Olin, the People’s Commissar for the Economy; and Silvia Lenka, an art student who is also the president’s lover. One of the artists whose work is displayed is Ludwig Kirchner, who was denounced as a counter-revolutionary and has since been arrested and sent to a re-education camp.

In stark contrast to the lavish event with liveried attendants serving caviar, lobster, smoked salmon, champagne, vodka and French wine, the next chapter introduces us to Maria Kirchner, Ludwig’s wife, as she stands in a long queue to get food, food which is obtained with ration cards and is often not even available. She has to feed not only herself but her daughter Lia.

We move among all these people and the way they cope with the regime. Helena’s partner Ruth Meyer has been put in charge of an orphanage (where Silvia grew up when her biological mother gave her up for adoption). Ruth is worried that Zdanhov is sexually abusing some of the boys and wants to find a way to stop him. Silvia wants to find her birth parents and to understand why they gave her up. Olin has a disabled son whom he is trying to care for. Ludwig is trying to survive in the re-education camp, which is ruled, not by the authorities but by Koba, a criminal who pulls the strings. And Lia, Ludwig’s daughter, turns out to be crucial to the plot, even though she stays in the background for most of the book.

In the meantime, there is a revolution brewing—small-scale, but large enough to do some serious damage to an already faltering regime. Then Gorbachev declares Perestroika, which deals the final blow and the regime collapses.

But what will replace the dictatorship? Will it be genuine democracy, or will it be a kleptocracy with people like Koba in power? Will those in power in the old regime pay for their crimes?

This is a multilayered novel about power and revenge, and the way ordinary people cope with impossible circumstances. Some fight it, some go along with it, and others do whatever it takes for them to survive. The individual stories that play out over the course of the book are absorbing. I cared about the characters—many of them, anyway—and because each one of them has a chance to be in the limelight, you understand what drives them, even though it does not excuse their actions. It is interesting to see how they react to the monumental changes that their country is going through.

The book seems to reflect what happened in several communist countries—but in many ways, also reflects our current times with its dictators, both actual and aspiring, and the growing inequality between people.

The epigraph is from John 18:38: “What is truth? Pilate asked Jesus”. Perestroika centres around telling the whole truth about a country and its rulers. Because João Cerqueira does this through the lives of its citizens, you get a detailed picture of what life was like, both for the poor and the rich. It is a bit expository in the beginning—some of the conversations serve merely to set the scene—but it picks up soon enough. There are a lot of characters to keep in mind but there is a list at the beginning of the book, which is useful.

My gripe is the title, which does not do justice to the book. It makes it sound a little lurid, which the book isn’t.

Perestroika is an interesting kaleidoscope—or more accurately, a mosaic—that is worth reading.