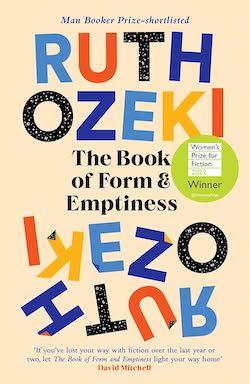

Published by Canongate, 2021, 550 pages.

“Stories never start at the beginning, Benny. They differ from life in that regard. Life is lived from birth to death, from the beginning into an unknowable future. But stories are told in hindsight. Stories are life lived backward.”

“Things speak all the time, but if your ears aren’t attuned, you have to learn to listen.”

Twelve-year-old Benny is hearing voices. Things speak to him: pencils, window panes, glass ornaments… It all began when his father Kenji died. It was an avoidable accident: one night, Kenji, a clarinet player, was coming home from playing in a jazz band when he fell down in an alleyway. High on drugs and drink, he decided to lie there, and a truck carrying chickens ran over him.

Kenji’s death leaves Benny (named after Benny Goodman) and Benny’s mother Annabelle bereft and completely lost. Annabelle works as a “scissor lady” in a media-monitoring agency, cutting out articles that might be of interest to the agency’s clients. Annabelle’s way of coping with Kenji’s death is to hoard, to fill the emptiness in her life with things. Soon the house is filled to bursting with old newspapers (she is working from home now), and the odds and ends she buys. She finds it almost impossible to engage with everyday life. She cannot let go of her grief, and this translates into an inability to throw anything away—in fact, her shopping grows into an addiction.

Benny, with his new-found ability to hear inanimate things speak, is going crazy with all the objects in the house. He keeps his room tidy but the minute he steps out of it, he walks into a maelstrom of voices. Every single thing seems to have a story or a complaint that it wants to share with Benny. He cannot escape the voices; even when he opens the fridge, he hears “the groans of moldy cheeses, the sighs of old lettuces”. The voices continue at school: a windowpane won’t stop wailing when a bird flies into it, and a pair of scissors wants him to walk up to his teacher and stab her. Unable to resist, he walks up to her but plunges the scissors into his own thigh.

This incident has him admitted into the psychiatric ward of a children’s hospital. There he meets Alice, known as The Aleph, an older girl with a ferret and a habit of leaving cryptic notes for others to find, who becomes his friend. After Benny is released, he spends all his time in the library: it is the only place that the voices go quiet. The Aleph finds him there, and introduces him to the B-Man, a homeless Slovenian poet in a wheelchair.

Meanwhile, Annabelle is struggling to cope. Digital media has made her job almost redundant, but she still has a job—her living room is host to a huge console of screens as she finds articles for her firm. Benny and she argue constantly, and the house is a mess. There is no space anywhere—no space in the kitchen to eat, dirty dishes in the sink, bags of stuff all over the house, and no milk in the fridge.

Things come to a head when she is threatened with eviction, and she discovers Benny has been lying to her and going to the library instead of to school.

This is a book about people faced with devastating loss who try and cope in their own ways. It isn’t just Benny and Annabelle who are grieving: Aleph has been through her traumas too, as has the B-Man. The touch of magic realism adds to the book. Magic realism—in this case, the voices of everyday objects—works only when you can believe in the characters and the story. The way Ruth Ozeki has drawn the characters makes you care about them. They are flawed and very human, and I found myself rooting for them.

I wasn’t sure what to expect from this book when I started, and it took me a while to get into. The narrator of the story is the Book itself—with occasional interjections by Benny. In a novel, it is, in a sense, always the book that tells the story. Ozeki has turned this into an interesting conceit by making the Book a character in its own right. The Book is the keeper of Benny’s memories and his history. “How much of this do you remember, Benny?”, it asks at one point. “Or have you blocked this all out, too?” It is the Book that helps him to make sense of everything that has happened to him.

Benny meets the Book for the first time in the library’s basement. When he hears the voice of the yet-unwritten Book, down in the depths of the library, you feel a frisson—this is the voice of all those books we carry within us, waiting to be written.

This is also an ode to public libraries and their power to save us, to give us a safe space where we can shelter from the turmoil of our lives. It is also a celebration of books and the way stories can help us find a way through grief and pain.

The Book of Form and Emptiness is a moving and surprising novel, and one I thoroughly enjoyed.