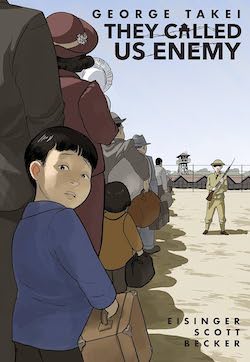

Published by Top Shelf, 2019, 208 pages.

After the attack on Pearl Harbour by the Japanese on 7 December 1941, the US government declared that all people of Japanese origin were “enemy aliens”, including those who were US citizens. They were rounded up and incarcerated. The assumption was that their race made them “nonassimilable” and their loyalty was to the Japanese emperor rather than the US.

One of those who was incarcerated was four-year-old George Takei.

Takei still remembers the US soldiers hammering on the front door of his house in Los Angeles, his parents packing hastily, and the fear and bewilderment he felt, all those decades ago. The family—Takei, his parents and his younger brother and baby sister—were hustled out of their home, taking only what they could carry in a couple of suitcases.

At first, the families were housed at a racetrack. His parents, who had worked hard to buy a two-bedroom house, were now crammed with their children into a smelly horse stall. As children, Takei and his brother thought it was an adventure, only realizing the injustice of their situation when they were older.

A few months later, the families were moved to a camp, where they stayed for the next few years. The conditions were better than at the racetrack—at least they had their own accommodation—but like all the other Japanese families, they lost everything they owned: their bank accounts were frozen, and their homes were occupied by others. In May 1944, they were moved to another camp, this time behind three layers of barbed-wire fences instead of one.

Even when they were finally released, Takei faced discrimination at school. His fourth-grade teacher would ignore him in class and watch him like a hawk during recess. When he is older, he wonders why she hated him so much. Did she lose a husband or son, killed by people who looked like Takei?

Through it all, Takei’s parents were a steady presence in his life, doing their best to protect their children from the worst of the experience. His father, in particular, was remarkable. In the camp, he became a representative of the Japanese, acting as an intermediary between the families and the authorities. In spite of everything he went through—the injustice and the humiliation—he never stopped believing in democracy, something he passed on to his son.

Later, as an actor, Takei became known for his role as Hikaru Sulu, helmsman of the Starship Enterprise in the original Star Trek series. Created by Gene Roddenberry, Star Trek resonated with Takei: for the first time, a television series had a multi-ethnic cast—including a Japanese-American as helmsman, a change from the usual roles Takei was offered as “buffoons, menials or menaces”. The series promoted understanding and dialogue to resolve differences. Takei also went on to become a strong advocate for the rights of immigrants and the LGBT community, and is a key player in Japanese-US relations.

His graphic novel is a memoir, focusing mostly on Takei’s childhood in the camps, but also as a young man trying to come to terms with what happened, and as a struggling actor who landed a role that changed his life.

Takei tells the story both from a child’s point of view and from an adult’s perspective. Because the book moves between timelines, it puts the events into context.

There are some poignant moments in the book. When Takei and his father are working for Adlai Stevenson’s campaign, they hear that Eleanor Roosevelt is due to visit Stevenson’s campaign headquarters. Takei is excited, but his father says he is not feeling well and goes home. Later, Takei realizes that his father did not want to meet the woman whose husband, FD Roosevelt, had issued an Executive Order to detain citizens of Japanese origin. In 2017, when Takei is invited to speak at the FDR Museum and Presidential Library, he tells the audience of his mixed emotions as he drives up the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Parkway.

This is an important book, and a reminder of a dark period in US history, a time when prejudice destroyed the lives of so many. Takei brings the book up to the recent past, where what happened to him as a child continues to happen to other immigrant families. They Called Us Enemy is a powerful memoir that still resonates today, as history carries on repeating itself.

Thank you for the review of this! I remember the buzz when it first came out but had forgotten all about it since. I don’t often read graphic novels, but this sounds like a really worthwhile one, about a subject that doesn’t seem to feature in many novels.

It is worth reading. Glad my review reminded you of it!