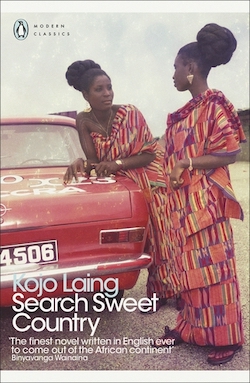

Published by Penguin, 1986, 351 pages.

“Back in the streets Accra had one eye shut: at nine o’clock, the taxis were driving towards sleep; and with the open eye, with the one bright headlight, they moved to the cines, the wake-keepings, the spiritual churches, the still-talking compounds, the society meetings, the discos, the night-classes, the late journeys, the night kenkeys, the kelewele, and the evening profits.”

Search Sweet Country is a loosely woven novel that follows several people living in Accra, Ghana. It is hard to pin down: a mix of social satire and magic realism, with no clear plot. Instead, characters drift in and out of the novel, and not all their stories have an end. Add to this Kojo Laing’s use of language—overblown, mixed metaphors—and you can see why it is difficult to describe this book.

In spite of all this—or actually, because of this—there is something compelling about Search Sweet Country. It is a portrait of Ghanaians and of Ghana in the 1970s; it feels like the people and the country are all looking for something.

There is Beni Baidoo, a man set on founding his own village, pestering his friends for help in realizing his dream. Through Baidoo, we meet the others. “He brought to friendship a fine quality: nuisance value; and then flowed with his one obsession in and out of the lives he met…”

His friends include Erzuah Loww and his son Kofi, a dreamer, who is in love with Adwoa Adde, a witch. Kofi’s mother Maame had left when he was a child, but now that Kofi has a son of his own, she is back in their lives. She is not really welcome, especially by Ezruah, but she is determined to get to know her grandson.

Sackey, Professor of Sociology, seethes with anger and frustration at the world. Sackey’s wife Sofi has taken his anger for years and has finally found a way of fighting back. She “had armed her muteness. And was at last becoming expert in withdrawing just when she could provide some sort of inner walking stick for this stumbling man.”

Sackey thinks that if only he could become a farmer, he would be happier. This takes him to Owula ½-Allotey, farmer and herbalist—“the oddest farmer in the plains nearest Accra”. Allotey feels he has been divided in two (hence his name). He disappears from his fellow villagers’ “horizon of sense,…down into the subsky of sage, buffoon and madman”.

The book’s plot—such as it is—involves illegally importing racehorses. The Commissioner of Agriculture wants to bring in these horses to start a private race club—passing them off as farm horses, destined to pull ploughs and increase Ghana’s food production.

The Commissioner thinks Dr. Boadi, a teacher with big ambitions, would be perfect to help him with his scheme. Boadi is a smooth presence, so smooth that when he was born, his mother almost did not realize he was out. Boadi jumps at the chance to work with the Commissioner. “For after all who in Ghana knows the difference between a racehorse and farmhorse like the Clydesdale?”, Boadi asks. He tasks Kojo Okay Pol—whom he sees as clever enough for the job but also naïve enough to buy the story—with ensuring that all goes smoothly.

But, at the airport, things do not go according to plan. The porters complain that the boxes, which they have to carry, are too heavy, and let a couple of them drop (they are also curious to see what’s inside). The boxes open, the horses escape, and all hell breaks loose.

The fiasco regarding the horses ends up involving many of the characters, including Kofi Loww, who happens to be there and witnesses the escape.

It is not just the petty corruption of officials that Laing exposes. It is a co-opting of the general population. A large crowd, organized by Bishop Budu and his assistant Osofo Ocran marches to the Castle, the seat of government, to protest peoples’ living conditions and the country’s politics, and calling for sanity in their lives. As the protesters near the Castle, they are met by police, and are told by an officer that the Head of State has a message for them. The message is food for the hungry, a feast laid on to distract the crowd. Although the police are willing to use force if necessary, the people are delighted by the food on offer. They abandon the protest, and their march turns into a picnic. Laing is scathing about the reluctance of the general population to do something to improve their condition. “Accra…was the bird standing alive by the pot that should receive it, and hoping that, after being defeathered, it would triumphantly fly out before it was fried.”

Laing takes language and bends it to his purpose, creating images in a way I haven’t seen before. “Dr Boadi had risen once or twice during Sackey’s outburst, but with a great effort he pushed the gates of his smile open. Pol saw his teeth singly, each one sharp with suppressed anger…”

I love the way Laing uses humour. A church is so poor that it has “to wait for two lizards to cross tails before it had a Cross”. Kojo Okay Pol, an optimist, is “the monkey that believed he could climb down his own tail in any emergency.” Okay Pol’s room is so neat “that the chairs sat with crossed legs”. Allotey meets his brother Kwaku, “with his teaspoon mouth holding out little measurements of his smile, part-welcoming part-resenting him.”

I had a hard time getting to grips with this book. I actually read it twice, and the second time around, I learned to go with the flow and enjoy Laing’s often overblown language. I felt I was a part of these people’s lives for a while, and once the book ended, their lives simply went on.