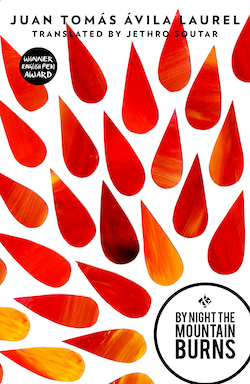

Translated from Spanish by Jethro Soutar

Published by And Other Stories, 2014, 275 pages. Original version published in 2008.

“[F]or our island was all alone at sea and there was no other land we could join forces with to combat our lack of everything. It was around then that I realised we islanders had no one to depend on but ourselves. That’s to say, we were on our own out in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean.”

This is the story of a boy growing up on an island where people did not have a lot to live on. The island is unnamed, but is probably based on Annobón Island, a province of Equatorial Guinea. The narrator looks back at his childhood on the island.

The book starts gently enough, with a description of how a canoe is built: the felling of the tree, the hollowing out of the log, and then the whole village joining in to pull it to the beach, where it will be finished. It sets the scene: this is a community where people work together, and families rely on their neighbours to help out in times of hardship, where the villagers take from nature only what they need.

From time to time, ships from “foreign nations” visit the island’s local waters to fish. Some of them steal the fish and drive off the local fishermen; others—the “friendly nations”—give the islanders provisions in return for their fish: soap, kerosene, matches, food and tobacco.

The narrator lives in a two-storey house with his family: his mother and aunts (who are referred to as “our mothers”), his cousins, grandmother and grandfather. The children’s fathers have gone away to a place you go to by boat and have not returned. The grandfather barely speaks and never leaves the house—the narrator isn’t sure if he even eats. Only the men go fishing, so this means there is no one to go out and fish for the family, who survive on cassava bread, salt and chillies, unless they are given fish by the fishermen or a family member.

The house is near the beach but, for some reason, faces away from it, towards the mountain. The boy cannot understand why this is, and why his grandfather spends his day sitting on the balcony, staring at the mountain.

School, when he finally goes, is something the boy sees as a punishment. He is made to learn Spanish, a language that is not his. The teaching is by rote, so the words with which the children memorize the alphabet are words they do not understand, and refer to things that mean nothing to them, like dice, donkey and poppy.

And then one day, two women go up to their cassava fields, and are careless with fire. Before they realize it, the mountain has caught fire, and everyone’s fields are burned down. The women rush back, not daring to own up to their mistake. The blame falls on someone else, a “she-devil”. These were women who, for no particular reason, were seen as consorting with the devil, who gave them special powers (reminiscent of the hunting of witches in Europe and North America).

What follows is horrible, as the villagers turn on the woman. The boy sees it all, and it is something he will never forget. But already, at that young age, he questions the actions of the adults and is mature enough to see that the woman could have been saved, and that maybe, this act led to all the problems that beset the islanders later, such as the cholera epidemic that devastates the village.

And then there are the evil ones, who come out at night. “In the south village, nothing gave off any light, and I think most people thought like me and preferred there not to be a moon, one of those bright full moons. Because they leave you exposed. I couldn’t go anywhere on my own on moonlight nights, for I knew evil things could see me from far away. And in that south village there was no noise of any kind at night, other than the cricri of the crickets and a noise the bats made with their throats.”

This book reads like an oral narrative. There is no dialogue, and the stories the narrator tells loop back, much in the way we remember. The narrator recounts an incident, and then goes back to it later in the book. The level of detail and the repetition bring it all to life: you feel the hunger and can taste the dry cassava bread, and feel the despair of the villagers as they battle a cholera epidemic that they barely have the resources to fight.

This vividly described book pulls you into the boy’s world. I love the way that Juan Tomás Ávila Laurel builds the narrative, and layers it, going back and adding detail to a story already told. Through the language (beautifully translated by Jethro Soutar), you get a sense of the rhythms of the everyday life of the village.

Pingback: The Best Books of 2023 – Talking About Books