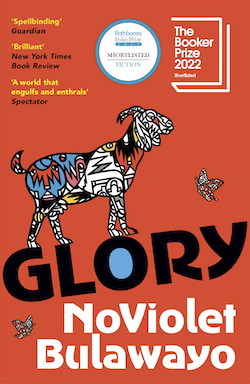

Published by Viking / Chatto & Windus, 2022, 403 pages.

“The Father of the Nation…was at an age when what was most important to him was to be left alone, and besides, those who know about things said the state of affairs inside his head wasn’t unlike a tumultuous country without a clear leader.”

Jidada, Independence Day. A crowd of animals is waiting in the hot sun to hear the leader of the nation give his speech, a leader who has ruled over Jidada for four decades. The crowd—pigs, goats, cats, cows, geese, hens, donkeys and sundry animals (“mals”)—are hot and restless. Defenders armed with batons, guns, tear gas canisters and “such typical weapons of defending” guard the gates to make sure no one leaves.

A couple of pages into the book, you know immediately where you are. NoViolet Bulawayo has taken the premise of Animal Farm and set it in Zimbabwe. Jidada is a thinly disguised stand-in for the country, and the leader—the Old Horse—is Mugabe, aging and slowly losing his grip.

The first chapter sets the scene. The Old Horse is accompanied by his young ambitious wife, the donkey Marvellous, walking “with the unquestionable swagger of power”: Jidada’s First Femal, whom everyone called Dr. Sweet Mother (she demanded, and was awarded, “a PhD in sociology before you could say diss for dissertation”). On the stage with the couple is the vice president, Tuvius Delight Shasha or Tuvy as he is known, an old horse too, but not as old as the leader. Tuvy has ambitions of his own and resents Marvellous, a femal who has known nothing of the bloody wars that he and the Old Horse have fought side by side.

During the Old Horse’s address, a dozen naked femals—the Sisters of the Disappeared—storm the stage, defiantly shouting “Bring back Jidada’s disappeared!” They are dragged off by the Defenders—the dogs who guard the Father of the Nation and are his enforcers.

But “the animals in the square heard the roaring right in their intestines, where lived the memories of disappeared friends and relatives or relatives of friends and also known and unknown Jidadans they’d read about in newspapers and on social media, yes, tholukuthi heard the chants deep in their hearts, where also live the unanswered prayers, the bleeding wounds, the nightmares, the ceaseless anguish, the questions over loved ones, over known and unknown Jidadans who’d dared dissent against the Seat of Power only to vanish like smoke, never to be seen again.”

Then the politics start to play out—the rivalry between Marvellous and Tuvy leads to Tuvy’s humiliation as the Old Horse strips him of his title and banishes him. But Tuvy does not remain in the wilderness for long. He is summoned by the generals—pit bulls—and together, they stage a coup that overthrows the Old Horse.

Meanwhile, a young goat, Destiny, returns to Jidada after a self-imposed exile and brings with her hope that things could change. After all, Tuvy has promised to call #freeandfairelections, so anything could happen. If you have been following the events in Zimbabwe, then you know what did happen—the elections were neither free nor fair. But in Jidada, Destiny becomes the catalyst of change.

This brief synopsis does not do justice to the richness of this book. The characters are vividly drawn—not just the leaders, but the ordinary Jidadans: Simiso, Destiny’s mother, driven almost mad by her daughter’s disappearance and bearing traumas of her own; the Duchess, the wise cat; and Destiny herself, carrying memories that she would rather forget, but strong enough to imagine a new future for Jidada.

Bulawayo does not mask the brutality of a regime that is built on fear: the intimidation, the violence and the indiscriminate killing. And the courage of those who refuse to be cowed and who dare stand up to the regime. She takes us back to the Gukurahundi, the genocide that took place in Zimbabwe from 1982 to 1987.

Bulawayo tells the story with biting satire and humour. The Father of the Nation sneaks out in disguise to walk among his people and is horrified by the poverty and discontent that he finds—he actually believes his own myths about a contented, prosperous people. Tuvy’s woollen scarf that he wears constantly, no matter what the weather, was given to him by his shaman, who tells him it would protect him from everything.

This is a powerful and beautifully written book. Bulawayo uses language in a way that I have not come across before: call and response, repetition and exaggeration. It is interspersed with tweets and snippets of conversation as the citizens of Jidada argue about their leaders and the state of their nation. The writing feels conversational—Bulawayo uses the word tholukuthi throughout the book, a Shona word that can mean “you find that” or “in truth”.[1]

Glory is heart-breaking, brutal, funny and ultimately uplifting. It imagines an alternative future for Zimbabwe—a future that might yet come to pass.

I absolutely have to add Glory to my list.

I have visited Zimbabwe and was aghast at the political situation and the fear of the citizens talking about Mughabe .

Excellent review Suroor.

Thanks, Sonia. It was one of the best books I read this year. Quite unlike anything I’ve read before.

Pingback: The Best Books of 2023 – Talking About Books

Pingback: Best Books of 2025 – Talking About Books

Pingback: Stepping through the Looking Glass: A Journey through Speculative Fiction – Talking About Books